In August 1864, on Spring Hill Station between Goroke and Natimuk, the Duff children - Isaac 9, Jane 7 and Frank 3 were asked to collect broom (tea-tree branches) for sweeping the hut floor. They became lost and wandered further into the Nurcoung scrub.

Their parents began searching and were joined by their neighbours.

On the 8th day, Aborigines from other stations - King Richard, Red Cap & Fred - joined the search. In the late afternoon of the 9th day the children were found.

The children had spent over a week without food or water, and walked nearly 100 kilometres.It was Jane's selfless attitude in caring for her younger brother Frank which sparked the interest of the nation.

Jane's schooling was paid for by one of the searchers and neighbouring squatter Alexander Wilson of Vectis and Longerenong homesteads.

Jane married George Turnbull on 24th June 1876, and reared 11 children (5 predeceased her). When George died of fever, Jane was left in troubled circumstances. She died at Horsham on 20th January 1932.

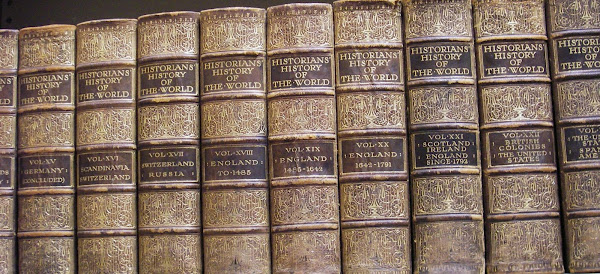

The story was told in the "Fourth Book" of the Education Department's school reader.

An appeal to Victorian school children raised money for a headstone over her grave, and to a memorial (by the roadside at the Jane Duff Highway Park near Duffholme) to her 1864 endeavours. Unveiling the memorial, Mr Graham declared her importance to a national self-image of the pioneering legend. Stating that Jane's actions were part of the wider contribution by women to opening up the land and played a part in the development of the Australian identity.

An appeal to Victorian school children raised money for a headstone over her grave, and to a memorial (by the roadside at the Jane Duff Highway Park near Duffholme) to her 1864 endeavours. Unveiling the memorial, Mr Graham declared her importance to a national self-image of the pioneering legend. Stating that Jane's actions were part of the wider contribution by women to opening up the land and played a part in the development of the Australian identity.The plight of the Duff children has been covered in art and story by a number of people over the years. In September 1864, well-known engraver Nicholas Chevalier, working for the Illustrated Melbourne Post, drew Jane caring for her brothers.

In the 1970s Peter Dodds made the film version of Lost in the bush on location west of Mt Arapiles and used local talent in the roles. Famous goldfields artist S.T. Gill painted the finding of the Duff Children in his Australian sketchbook. And equally famous - artist William Strutt (who sketched the Burke & Wills Expedition, and painted the epic Black Thursday bushfire) in 1901 wrote Cooey, or, The Trackers of Glenferry - a version of the story and illustrated it with beautiful watercolours and sketches.

Famous goldfields artist S.T. Gill painted the finding of the Duff Children in his Australian sketchbook. And equally famous - artist William Strutt (who sketched the Burke & Wills Expedition, and painted the epic Black Thursday bushfire) in 1901 wrote Cooey, or, The Trackers of Glenferry - a version of the story and illustrated it with beautiful watercolours and sketches.

The story has been told in rhyme for the young, but the most comprehensive retelling is L.J. Blake's Lost in the bush, which includes the local history surrounding the actual event.

Now, another author has entered - Stephanie Owen Reeder has just published Lost! a true tale from the bush (the cover is at the beginning of this post). This was inspired by Strutt's Cooey, and features many of his illustrations. What makes Stephanie's retelling different is that she has finished each chapter with an informative section on how children lived in the 1860s, much of it illustrated with works from the National Library's Picture Collection.

Dick-a-Dick (traditional name Djungadjinganook or Jumgumjenanuke, but also known as King Richard) (Died 3 September 1870) was an Australian Aboriginal tracker and cricketer, a Wotjobaluk man of the people who spoke the Wergaia language in the Wimmera region of western Victoria, Australia. He was a member of the first Australian cricket team to tour England in 1867-68. In 1864 he helped track and rescue three children - Isaac, Jane and Frank Duff - lost in the bush near Natimuk on the edge of the Little Desert for nine days. After the main search was cancelled due to rain obliterating their tracks, the children`s father and three Aborigines including Dick-a-Dick successfully tracked and found the children. The children had survived through the resourcefuless of seven year old Jane Duff. Dick-a-Dick was lauded a hero and subsequently called King Richard.

ReplyDeleteThere is a memorial to Dick-a-Dick beside the Jane Duff one at Duffholme, commemorating his role as a cricketer and tracker (http://www.flickr.com/photos/25245971@N08/7276298652/). He was also responsible for tracking & finding another lost girl at Yanipy in 1883. He was called King Richard as he was the elder son of King Balrootan of the Nhill tribe.

ReplyDelete